What is a Pulmonary Nodule?

A pulmonary nodule (lung nodule) is a small round or oval finding in a lung that shows up as a “spot” or “shadow” on CT scan or x-ray. It measures up to 3 centimeters in diameter, and if larger, is called a lung mass. Lung nodules are common (especially in smokers, and are typically benign (not cancer). Rarely, these nodules may be malignant (cancerous), including an early lung cancer.

About Pulmonary Nodules

Nodule Factors

Nodule density- Lung nodules are divided into three types: solid, ground glass, and part-solid (or subsolid).

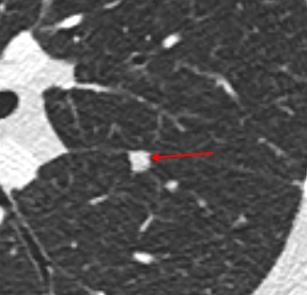

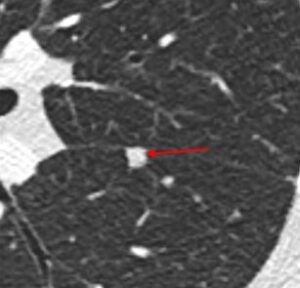

Solid. A solid nodule is defined by having the same density as the blood vessels in the lung.

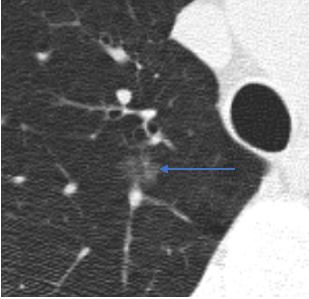

Ground glass. A ground glass nodule is more dense than

normal lung but less dense than blood vessels.

Part-solid. Part solid nodules have both ground glass and solid components.

Assessing Risk

In most cases, a lung nodule is not cancer. The risk of having cancer increases with the following:

• Older age

• Larger size

• Smoking

• Having a family history of lung cancer

• Having previous lung cancer

• Growth or irregular borders (i.e., spiculation)

• Having part-solid or ground glass nodules

• Upper lung location

Further Steps for Management

We recommend discussing further steps with your provider. Specifically, management may include obtaining your medical history and performing a physical examination. This may be followed by imaging exams such as CT scan or PET-CT scan. From there, additional tests may be needed.

Recommendations

FOR SOLID NODULES <6MM:

These nodules are most likely benign. The decision for additional follow-up should consider patient’s risk profile and preferences.

FOR SOLID NODULES 6MM – 8MM:

Nodules 6-8 mm pose a slightly higher risk of malignancy. Recommended time frames for follow-up imaging include 3-6 months and 6-12 months depending on risk, nodule and patient’s characteristics. Fuller assessment of the patient by a specialist or multidisciplinary clinic is needed to discuss patient’s risk profile, preferences and benefits of alternative management strategies.

FOR SOLID NODULES >8MM:

Nodules >8mm pose a higher risk of malignancy. Referral to a specialist or multidisciplinary clinic to discuss patient’s risk profile, preferences and benefits of alternative management strategies is recommended.

FOR GROUND GLASS NODULES:

Recommended time frame for the initial evaluation of ground glass or part-solid nodules ranges from 3 to 6 months, with shorter time intervals for patients with a higher pretest probability of malignancy (added risk and nodule characteristics). For persistent nodules, referral to a specialist or multidisciplinary clinic to discuss patient’s risk profile, preferences and benefits of alternative management strategies is recommended.

About Pulmonary Nodules

Patient Factors

The context in which a nodule is discovered plays a key role in the differential diagnosis of the nodule and what type of follow-up is needed.

Incidental nodule. An incidental nodule is defined as a pulmonary nodule that is identified on an imaging study (CT, CXR, PET-CT) done for another purpose (e.g. pain).

Nodule identified in a patient with active malignancy. These nodules are excluded from expert society guidelines(1). The need for, and frequency, of follow-up will depend on the specific risk of metastatic disease from the patient’s primary malignancy and should be discussed with the patient’s oncologist.

Patient age. The risk of malignant pulmonary nodules in younger patients is clearly very low, although the specific risk is not well defined. In light of this, some nodule guidelines specifically exclude patients younger than 35 years of age(1). Whether young patients need any follow-up is not specifically addressed by these guidelines.

Nodule Factors

Nodule density. Pulmonary nodules are divided into three densities: solid, ground glass, and part-solid (the latter two may be grouped into subsolid).

Solid. A solid nodule is defined by having the same density as the blood vessels in the lung.

Ground glass. A ground glass nodule is more dense than normal lung but less dense than blood vessels.

Ground glass nodules may occasionally have internal cystic lucencies or heterogeneous density, factors

that increase the risk of malignancy; however, these should still be described as ground glass nodules.

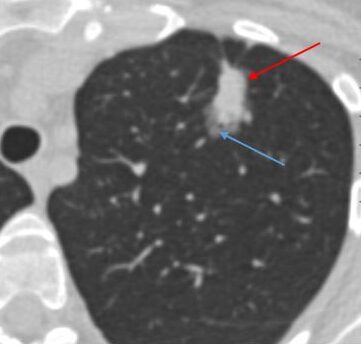

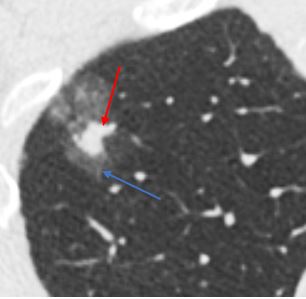

Part-solid. Part-solid nodules have both ground glass and solid components.

Solid nodules have the lowest risk of malignancy, while part-solid nodules have the highest risk(2). Solid nodules most commonly represent benign intrapulmonary lymph nodes or noncalcified granulomas, with a low risk of lung cancer of around 1% overall(2). Approximately one quarter to one third of subsolid nodules are inflammatory and will resolve(3). Many of those that remain represent lesions along the adenocarcinoma spectrum (atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma)(4). While they have a high risk of malignancy, subsolid nodules that are malignant are generally indolent, with slow growth rate and a low risk of metastasis or recurrence after surgery(5).

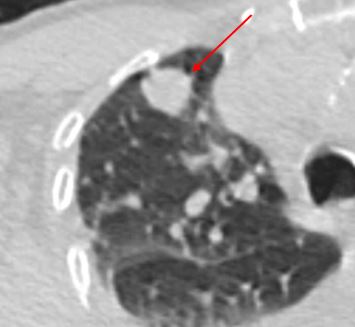

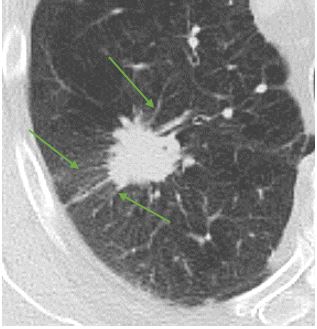

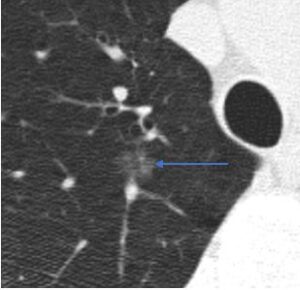

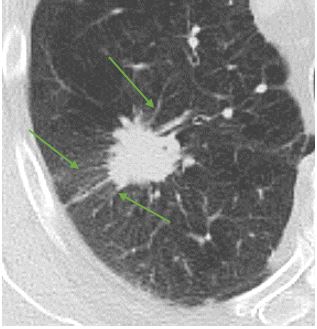

Nodule margins. Perhaps the best-known nodule risk factor for lung cancer is spiculation, which refers to linear extensions into the adjacent lung parenchyma with architectural distortion.

Solitary pulmonary nodule with spiculated margins (green arrows)

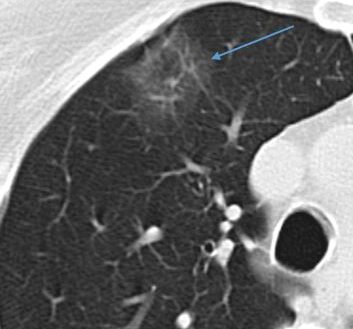

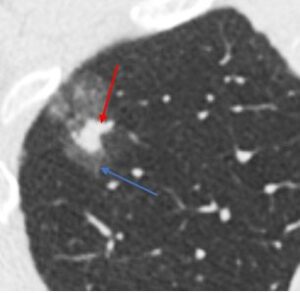

Intrapulmonary lymph node. One of the most common causes of solid pulmonary nodules are benign intrapulmonary lymph nodes. Intrapulmonary lymph nodes are typically located either along a pleural surface, or else within 1 cm of the pleura. Lymph nodes typically have oval or polygonal shapes with smooth margins.

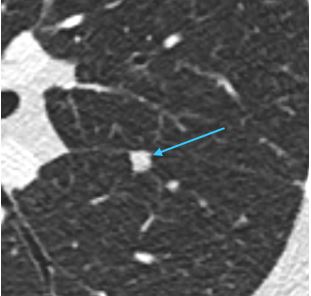

Nodules with smooth margins and oval or polygonal shape that are located along the fissures are referred to as perifissural nodules. These nodules have been shown to be benign in large series(6). Fleischner Society guidelines consider these to be benign and do not recommend follow-up(1). Other nodules with lymph node characteristics, particularly those that are subpleural but not perifissural, are almost always benign as well(7).

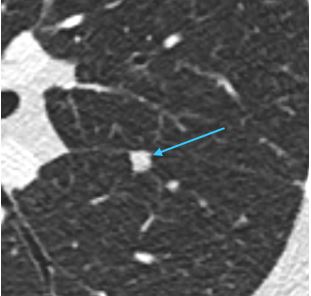

Example of a perifissural nodule (teal arrow)

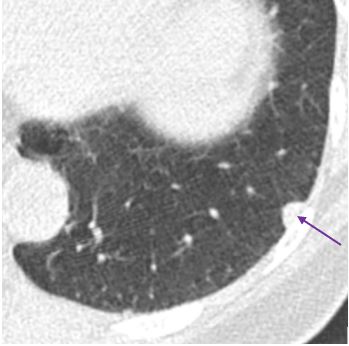

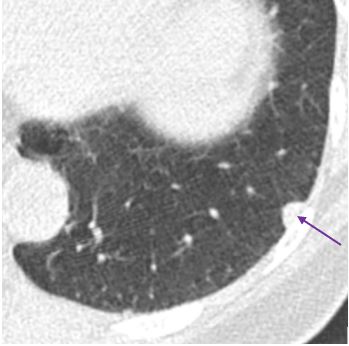

Example of a subpleural lymph node (purple arrow)

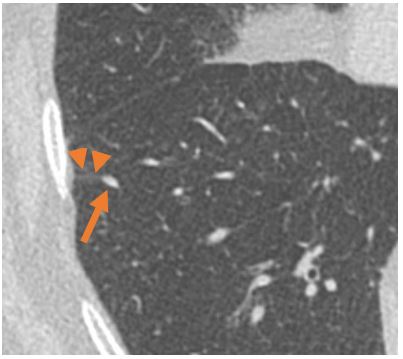

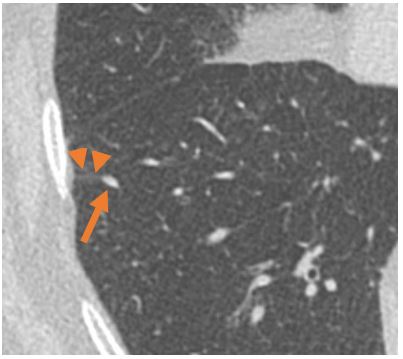

Example of an intrapulmonary lymph node (arrow) with septal connection (arrow heads) to the pleura

Nodule multiplicity. Much of the pulmonary nodule literature, including the Flesichner Society guidelines, refer to the “solitary” nodule. More than one discrete nodules are commonly present in a single patient. In general, follow-up recommendations should be directed to the largest or most suspicious-appearing nodule(1).

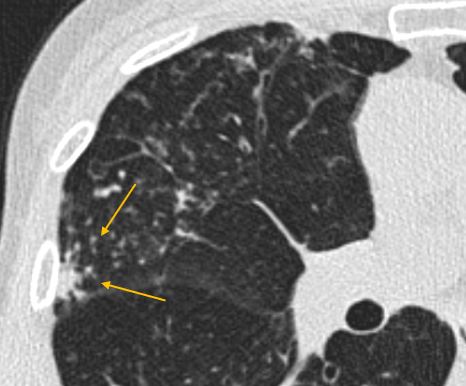

Clustered nodules, on the other hand, almost always indicate an infectious or inflammatory process(4). These are not directly addressed by most nodule guidelines, which really refer to discrete nodules(1,8). The presence of clustered nodules should prompt a differential diagnosis of an infectious process or inflammatory process. Whether specific imaging follow-up is needed for clustered nodules depends upon the constellation of imaging findings as well as patient history.

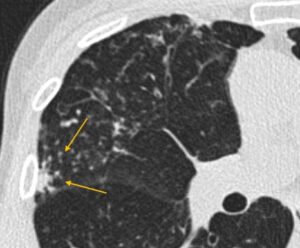

Clustered nodules at the site of infection (yellow arrows)

Nodule growth. Most guidelines do not reliably distinguish between nodules present on a baseline CT, nodules that have developed since a prior CT (new nodules), and nodules that have persisted over time (persistent or existing nodules). There is a slightly higher risk of lung cancer in new nodules (9,10). New nodules, particularly those without obvious inflammatory features, deserve closer surveillance, with smaller size threshold for follow-up, than those present at baseline(10,11). Of note, this recommendation is not incorporated into the Fleischner Society or ACCP guidelines but is present in the Lung-RADS guidelines for nodules detected at lung cancer screening(12). For persistent nodules, those that grow have a much higher risk of being malignant; however, there is a nonzero risk of malignancy even in stable nodules(10).

References

Assessing the risk for Lung Cancer

Risk for malignancy can be assessed in multiple ways including expert assessment by a specialist (radiologist, pulmonologist, thoracic surgeon, or oncologist). Alternatively risk assessment models may be used to assess patient’s risk of malignancy.

Below are commonly used risk calculators.

Based on Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer Study (PanCan).

Ref: McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:910.

The Guidelines

Evaluation of Individuals With Pulmonary Nodules: When Is It Lung Cancer?

Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines

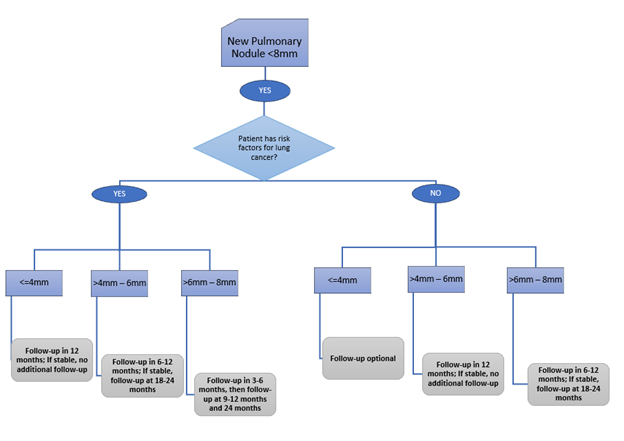

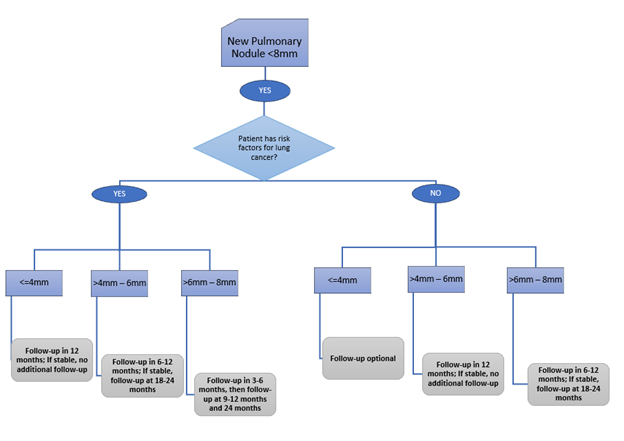

For SOLID NODULES <8MM, the ACCP Guidelines recommend…

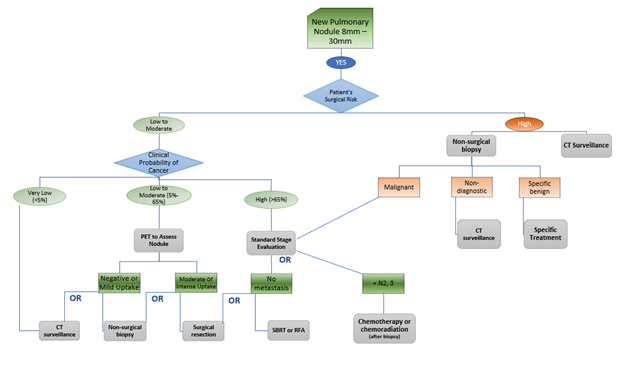

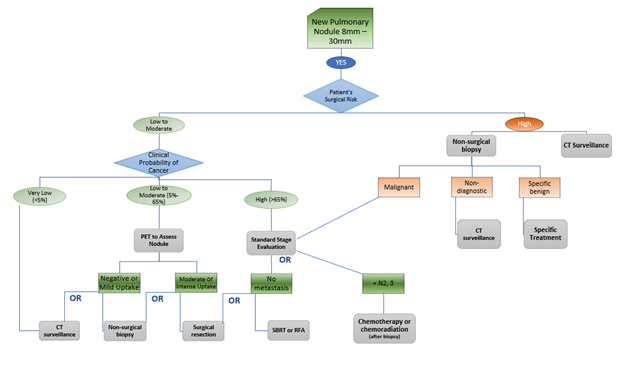

For SOLID NODULES 8MM – 30MM, the ACCP Guidelines recommend…

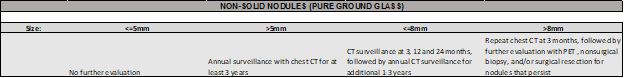

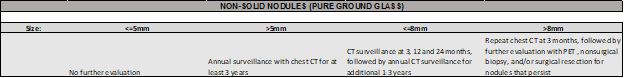

For NON-SOLID NODULES, the ACCP Guidelines recommend…

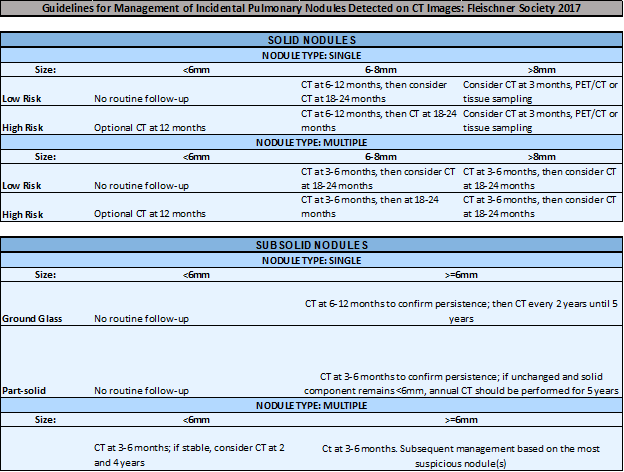

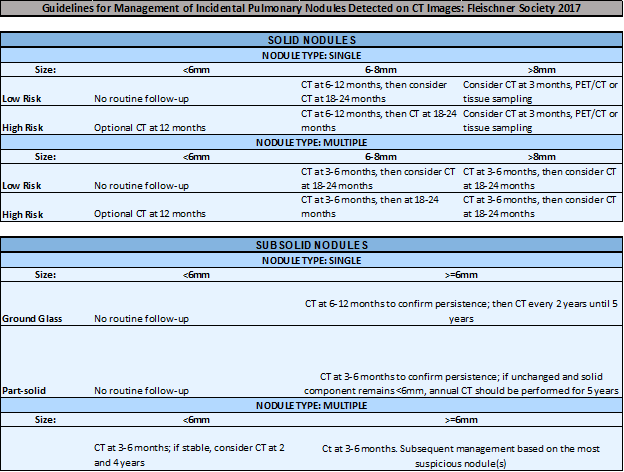

In brief, the Fleischner Society Guidelines recommend…

Recommendations For Reporting

- A subspecialty trained thoracic radiologist (expert) can make any recommendation based on their clinical judgment.

- The recommendation should be actionable and unambiguous.

- If the recommendation is for additional imaging, the modality and a timeframe (earliest/latest time identified) must be specified.

FOR SOLID NODULES <6MM:

Nodules <6 mm are most likely benign and the risk of malignancy is less than 5%. Need for additional follow-up should consider patient’s risk profile and preferences.

For more information on pulmonary nodule management, please visit www.cebi.bwh.harvard.edu/signatureinitivatives/ipn.

FOR SOLID NODULES 6MM – 8MM:

Recommended time frames for follow-up imaging include 3-6 months and 6-12 months depending on risk, nodule and patient’s characteristics. Alternatively, referral to a specialist or multidisciplinary clinic may be of benefit, particularly for higher risk patients.

For more information on pulmonary nodule management, please visit www.cebi.bwh.harvard.edu/signatureinitivatives/ipn.

FOR SOLID NODULES >8MM:

Nodules >8 mm pose high risk of malignancy. We recommend referral to a specialist or multidisciplinary clinic to discuss patient’s risk profile, preferences and benefits of alternative management strategies.

For more information on pulmonary nodule management, please visit www.cebi.bwh.harvard.edu/signatureinitivatives/ipn.

FOR GROUND GLASS AND PART-SOLID NODULES:

Recommended time frame for the initial evaluation of ground glass or part-solid nodules ranges from 3 to 6 months, with shorter time intervals for patients with a higher pretest probability of malignancy (added risk and nodule characteristics). For persistent nodules, we recommend referral to a specialist or multidisciplinary clinic to discuss patient’s risk profile, preferences and benefits of alternative management strategies.

For more information on pulmonary nodule management, please visit www.cebi.bwh.harvard.edu/signatureinitivatives/ipn.

About Pulmonary Nodules

Patient Factors

The context in which a nodule is discovered plays a key role in the differential diagnosis of the nodule and what type of follow-up is needed.

Incidental nodule. An incidental nodule is defined as a pulmonary nodule that is identified on an imaging study (CT, CXR, PET-CT) done for another purpose (e.g. pain).

Nodule identified in a patient with active malignancy. These nodules are excluded from expert society guidelines(1). The need for, and frequency, of follow-up will depend on the specific risk of metastatic disease from the patient’s primary malignancy and should be discussed with the patient’s oncologist.

Patient age. The risk of malignant pulmonary nodules in younger patients is clearly very low, although the specific risk is not well defined. In light of this, some nodule guidelines specifically exclude patients younger than 35 years of age(1). Whether young patients need any follow-up is not specifically addressed by these guidelines.

Solid. A solid nodule is defined by having the same density as the blood vessels in the lung.

Ground glass. A ground glass nodule is more dense than normal lung but less dense than blood vessels.

Ground glass nodules may occasionally have internal cystic lucencies or heterogeneous density, factors

that increase the risk of malignancy; however, these should still be described as ground glass nodules.

Part-solid. Part-solid nodules have both ground glass and solid components.

Nodule Factors

Nodule density. Pulmonary nodules are divided into three densities: solid, ground glass, and part-solid (the latter two may be grouped into subsolid). Solid nodules have the lowest risk of malignancy(2). Solid nodules most commonly represent benign intrapulmonary lymph nodes or noncalcified granulomas, with a low risk of lung cancer of around 1% overall(2). Approximately one quarter to one third of subsolid nodules are inflammatory and will resolve(3). Many of those that remain represent lesions along the adenocarcinoma spectrum (atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma)(4). While they have a high risk of malignancy, subsolid nodules that are malignant are generally indolent, with slow growth rate and a low risk of metastasis or recurrence after surgery(5).

Ground glass and part-solid nodules. Approximately one quarter to one third of subsolid nodules are inflammatory and will resolve(3). Many of those that remain represent lesions along the adenocarcinoma spectrum (atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma)(4). While they have a high risk of malignancy, subsolid nodules that are malignant are generally indolent, with slow growth rate and a low risk of metastasis or recurrence after surgery(5). Follow-up CT is recommended for ground glass and part-solid nodules to confirm persistence over time rather than an inflammatory process. Those that persist tend to grow very slowly over time, and long-term surveillance is recommended to monitor for growth of a solid component. The presence and size of a solid component correlates with risk for invasive cancer and more aggressive behavior. Experts and society guidelines disagree about the exact threshold, but part-solid nodules with sufficiently large solid components are generally referred for definitive treatment (e.g. surgical resection).

Nodule multiplicity. Much of the pulmonary nodule literature, including the Flesichner Society guidelines, refer to the “solitary” nodule. More than one discrete nodules are commonly present in a single patient. In general, follow-up recommendations should be directed to the largest or most suspicious-appearing nodule(1).

Example of a subpleural lymph node (purple arrow)

Example of an intrapulmonary lymph node (arrow) with septal connection (arrow heads) to the pleura

Solitary pulmonary nodule with spiculated margins (green arrows)

Example of a perifissural nodule (teal arrow)

Intrapulmonary lymph node. One of the most common causes of solid pulmonary nodules are benign intrapulmonary lymph nodes. Intrapulmonary lymph nodes are typically located either along a pleural surface, or else within 1 cm of the pleura. Lymph nodes typically have oval or polygonal shapes with smooth margins.

Nodule margins. Perhaps the best-known nodule risk factor for lung cancer is spiculation, which refers to linear extensions into the adjacent lung parenchyma with architectural distortion. Nodules with smooth margins and oval or polygonal shape that are located along the fissures are referred to as perifissural nodules. These nodules have been shown to be benign in large series(6). Fleischner Society guidelines consider these to be benign and do not recommend follow-up(1). Other nodules with lymph node characteristics, particularly those that are subpleural but not perifissural, are almost always benign as well(7).

Clustered nodules at site of infection (yellow arrows)

Clustered nodules, on the other hand, almost always indicate an infectious or inflammatory process(4). These are not directly addressed by most nodule guidelines, which really refer to discrete nodules(1,8). The presence of clustered nodules should prompt a differential diagnosis of an infectious process or inflammatory process. Whether specific imaging follow-up is needed for clustered nodules depends upon the constellation of imaging findings as well as patient history.

Nodule growth. Most guidelines do not reliably distinguish between nodules present on a baseline CT, nodules that have developed since a prior CT (new nodules), and nodules that have persisted over time (persistent or existing nodules). There is a slightly higher risk of lung cancer in new nodules (9,10). New nodules, particularly those without obvious inflammatory features, deserve closer surveillance, with smaller size threshold for follow-up, than those present at baseline(10,11). Of note, this recommendation is not incorporated into the Fleischner Society or ACCP guidelines but is present in the Lung-RADS guidelines for nodules detected at lung cancer screening(12). For persistent nodules, those that grow have a much higher risk of being malignant; however, there is a nonzero risk of malignancy even in stable nodules(10).

References

Assessing the risk for Lung Cancer

Several models exist that estimate the risk for a nodule being malignant.

Below are commonly used risk calculators.

Based on Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer Study (PanCan).

Ref: McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:910.

The Guidelines

Evaluation of Individuals With Pulmonary Nodules: When Is It Lung Cancer?

Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines

In brief, for NODULES <8MM, the ACCP Guidelines recommend…

For NODULES 8MM – 30MM, the ACCP Guidelines recommend…

For NON-SOLID NODULES, the ACCP Guidelines recommend…

In brief, the Fleischner Society Guidelines recommend…